European Economic

and Social Committee

When work is not enough for a decent life: ending in-work poverty in Europe

By Sotiria Theodoropoulou, ETUI

A job should be a reliable route to a decent life. Yet, across Europe, 1 out of 12 employed adults were classed as ‘working poor’ in 2024. EESC Info talked to European Trade Union Institute researcher Sotiria Theodoropoulou, who explained what it means to be working poor and how it differs from severe material and social deprivation. In Europe, the in-work poverty rate is highest in Luxembourg - a Member State with the highest GDP per capita.

What is the definition of the working poor? How do we differentiate in-work poverty from other forms of poverty, such as material deprivation?

The working poor (or those that are in work and at risk of poverty) are adults who have a job (and are thus ‘in work’), but are still income-poor (thus at risk of poverty). Their household income, after adjusting for the number and ages of those who reside within it, is below 60% of the country’s average income.

Being in work and at risk of poverty is classed as when the household income is low compared to other residents in the same country, and does not necessarily mean a low standard of living. It is different from being at risk of poverty or social exclusion (AROPE). AROPE is broader and includes anyone who is income‑poor, severely materially and socially deprived, or living in a very low work intensity household (where working-age adults are employed for 20% or less of possible working time).

The concept of in-work poverty differs from that of severe material and social deprivation. The latter refers to the enforced lack of at least 7 out of a list of 13 necessary and desirable items that would suggest leading an adequate life. The working poor therefore do not necessarily face severe material and social deprivation. However, living in a very low work intensity household, where the adults of working age work for 20% or less of the potential working time, is a key driver of in-work poverty.

What are the latest figures on the working poor in the EU? Are the numbers growing or stagnating compared to 5 or 10 years ago?

Differences in in-work poverty rates across countries remain stark: in 2024, Luxembourg topped the table (13.4%), while Finland and Czechia were the lowest (2.8% and 3.7% respectively) (see figure 1). The EU‑27 rate was down from a 2016 peak of 9.8%, showing some progress, but also that resilience or the ability to cope with economic pressure remains uneven. Some countries have been able to withstand high costs of living better than others.

What population groups are particularly at risk? What are the consequences these workers face?

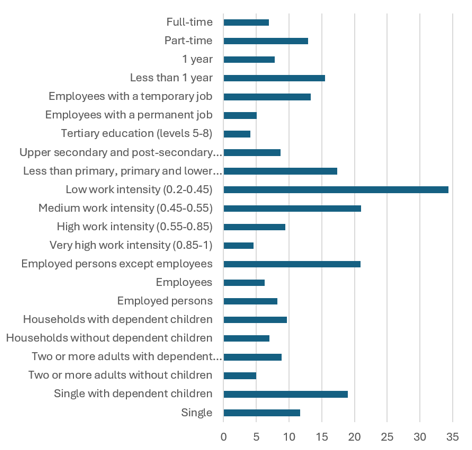

The in-work poverty risk clusters where household work intensity is low, contracts are non‑standard (fixed-term or part-time), skills are lower, or workers are migrants or single parents (see figure 2). Gendered care gaps and part‑time concentration add exposure for women in many Member States, underscoring that hours and household composition matter as much as hourly pay.

Figure 1. In-work poverty rates (%), EU-27 and Member States, 2024

Source: EU-SILC database (ilc_iw01 series)

Figure 2. In-work poverty rates (%) by socio-demographic and labour market characteristics, EU-27, 2024

Source: EU-SILC database (ilc_iw01/02/03/04/05/06/07/16 series)

What are the EU and Member States doing to combat in-work poverty, and is it enough? What more should be done?

The policies that can help reduce and mitigate in-work poverty are:

- adequate wage floors (a fair minimum wage for all workers) and wide bargaining coverage (where up to 80% of workers are covered by agreements that set their pay and working conditions);

- equal‑pay transparency and enforcement;

- fair contracts;

- predictable hours and full access to social protection for non-standard workers;

- universal, affordable childcare which allows more adults in a family to work or take more hours if they want; and

- adequate minimum‑income support with earnings disregards, which means that families are allowed to keep some benefits when they start earning, so that the second earner in the household actually gains money by working more hours.

EU law and guidance now provide a toolbox: the Minimum Wage Directive, the Pay Transparency Directive, the Platform Work Directive , and the 2023 Recommendation on adequate minimum income.

With ETS2 (the second EU emissions trading system) starting in 2027, the Social Climate Fund (2026-2032) can lower unavoidable energy and transport costs that keep low‑wage households below the line. Supporting higher educational attainment and the integration of migrant workers into documented employment can also alleviate the in-work poverty risk.

Last but not least, progress needs to be monitored by looking at how many working people are still at risk of poverty (in‑work AROP), breaking down the data by type of job contract, gender, and how much people in a given household are working. This helps make sure policies reach those who need it most. The information, collected through the EU’s main survey on income and living conditions (EU-SILC), should be published regularly and openly so everyone can see and check it.

Sotiria Theodoropoulou is the head of research unit ‘European economic, employment and social policies’ at the European Trade Union Institute in Brussels.