The number of Europeans unable to heat their homes may have fallen, but deeper structural barriers, such as the slow pace of renovation, patchy policies, and unequal access to financial support, continue to leave millions at risk. Ambitious legal and policy initiatives, such as the mandatory earmarking of funds to help people experiencing energy poverty, are already in place. Yet, the true test lies in translating this policy ambition into meaningful action, ensuring that support reaches those who need it most, writes Samuele Livraghi, energy policy expert at the Institute for European Energy and Climate Policy (IEECP).

By Samuele Livraghi, IEECP

At first glance, it may seem that the latest Eurostat figure on energy poverty in the EU marks some progress: in 2024, 9.2% of EU citizens were unable to adequately heat their homes, down from 10.6% in 2023. However, this apparent progress masks persistent vulnerabilities beyond this limited metric. In 2024, a combination of lower energy prices, moderated demand, information and awareness campaigns, grassroot action, and various efficiency investments has helped reduce the headline numbers.

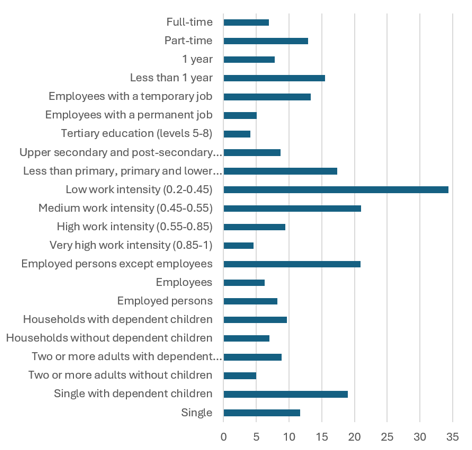

Yet, deeper structural barriers remain, including slow building renovation rates (below 1%), fragmented policy implementation, and uneven access to co-financing opportunities and green loans. Analysts caution that between 8% and 16% of Europeans may still be facing energy poverty. To further complicate this picture, many households experiencing energy poverty are not strictly income-poor: middle-income households with inefficient dwellings or high energy costs may also slip through social safety nets.

Moreover, both geographic and demographic disparities remain stark. In rural areas, not only do households often spend 7% or more of their income on energy, but also most rural homes were built before the 1970s. Many still rely on high-carbon fuels, with around 40 million rural households remaining off the gas grid, facing higher heating costs, limited access to cleaner energy options, and underinvestment in housing quality.

Is the current policy push translating into action?

The recast of the Energy Efficiency Directive (EU)2023/1791 strengthens the legal imperative to empower and protect vulnerable people experiencing energy poverty. Article 8(3) now mandates that a defined share of energy savings must be earmarked – or ring-fenced – to benefit priority groups (widely understood as low-income households, energy-poor households, renters and social housing inhabitants).

The deadline to transpose the Directive is 10 October 2025. In the latest Member States’ reporting, the ring-fencing clause (Art. 8(3)) still occasionally appears as a token statement rather than being backed by a binding budget or a clear pipeline of projects, which slows down much needed interventions. Some Member States lack the data granularity to target households effectively, or instead target ‘vulnerable customers’ with generic energy subsidies, social tariffs, or tax reductions, rather than structural retrofits. Moreover, several evaluations flag up the fact that efficiency measures have disproportionately reached better-off households, even though poorer households have less capacity to co-finance renovation.

If fully implemented, ring-fencing could bring a much-needed breath of fresh air to vulnerable households, who are often on the margins of policy discussions and measures. Households experiencing energy poverty would benefit from a dedicated pool of funding, ensuring that a portion of savings is explicitly channelled to them. In practice, this could mean:

Deep renovation or partial retrofit of the worst-performing homes, reducing energy bills by 30–50%, as envisioned within the EU Renovation Wave.

Targeted technical assistance, bundled with finance (loans, grants, on-bill repayment), to ensure vulnerable households do not face upfront barriers.

Prioritised deployment of interventions (insulation, heat pumps, photovoltaics) in low-income and social housing sectors, as also supported by the Social Climate Fund and Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (recast).

Enhanced monitoring and evaluation, ensuring that outcomes (reduced arrears, improved indoor comfort and health gains) feed back into policy adjustments, as planned both in the National Energy and Climate Plans, and Social Climate Plans.

In 2024, eleven Member States had already established energy poverty observatories, a fundamental step towards diagnosing and contextualising the issue. To further activate these strategies, policymakers, experts and practitioners must acknowledge that people and communities are at the forefront of these challenges and need to be heard. This is possible when their adaptive capacity is understood and harnessed, enabling us to determine whether and how households can translate efficiency gains into real every-day comfort improvements and greater resilience.

Are current tools enough under current pressure?

EU policymakers have assembled an impressive toolkit that should directly support the alleviation of energy poverty: dedicated provisions in the Directives on energy efficiency, buildings and renewables; the Governance Regulation of the Energy Union; Recovery & Resilience funding; EU cohesion and structural funds; and the Social Climate Fund.

But is this enough? Seventy-five percent of EU buildings are classified as poor energy performers, and many require capital-intensive deep renovation. For many households, co-financing or prefinancing, as well as administrative costs of renovation, remain prohibitive. The shared burden of financing often lands on national, regional or local authorities whose budgets are stretched. Yet these authorities are largely excluded from the process of developing Social Climate Plans, despite legal obligations for them to be involved.

A narrative of hope and demand

Amid these systemic gaps, there is reason for hope. Across Europe, local NGOs, social housing associations, energy cooperatives, municipal retrofit programmes and citizen-led ‘energy poverty labs’ are proving that change from the ground up is possible. These are the stories that must be elevated and amplified. If European institutions, Member States and civil society commit to prioritising structural equity, energy poverty can be addressed not just as a statistic, but as a transformative pathway to enhance citizens’ livelihoods and secure a better future for all – one that includes energy justice.

Samuele Livraghi is an energy policy expert at the Institute for European Energy and Climate Policy (IEECP), an independent non-profit research hub that turns scientific knowledge into practical advice for policymakers and organisations working towards a sustainable energy future. Most of his research has focused on energy poverty, policy evaluation, and inclusivity, through projects such as ASSERT, LOCATEE, RENOVERTY, and ENSMOVPlus. These projects allowed him to further explore the intersections between policy, society, economy and climate, applying analytical skills to underpin his research. They also gave him the opportunity to observe how energy poverty manifests itself across Europe and to document the implications of climate reporting.